Since 1836 most states have assigned electors based on the results of the states' respective general elections. Thus, electors typically vote for the winner of the state popular vote. Maine and Nebraska are the only two states that do not follow a winner-takes-all approach in which the candidate with the most votes receives all of the state's electoral votes. In practice, electors vote for the candidate who wins the popular vote in their state however several states do not require this. A federal court ruled in August 2019 that members of the Electoral College are not mandated to vote for the winner of their state's popular vote.

This was a win for faithless electors, which are Electoral College delegates who refuse to cast their votes for the presidential candidate their state has pledged to support. However, in July 2020 the US Supreme Court ruled that states do have the authority to require electors to vote for the state's selected candidate for president as determined by the results of the popular vote. This Supreme Court ruling affirmed the power of states, not individual electors, to assign electoral votes. Though voters may be unaware of the process, when they cast their ballots during the general election in November, their votes do not directly elect the president, but instead decide how the electors from their state will vote. The winner of the popular vote in each state, based on the number of actual votes cast by the general population in that state, is determined.

The electors for each state are generally obligated to vote for that candidate, therefore all of a state's electoral votes tend to go to the same candidate. A candidate can win the popular vote of the United States but not the presidency if the candidate fails to gain the majority of electoral votes. The winning candidate must receive at least 270 electoral votes to win the presidency. On the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December of the election year, the electors assemble in their respective states to cast their ballots and elect the president. In 2020 Trump contested the results of the presidential election after losing to Democratic candidate Joe Biden.

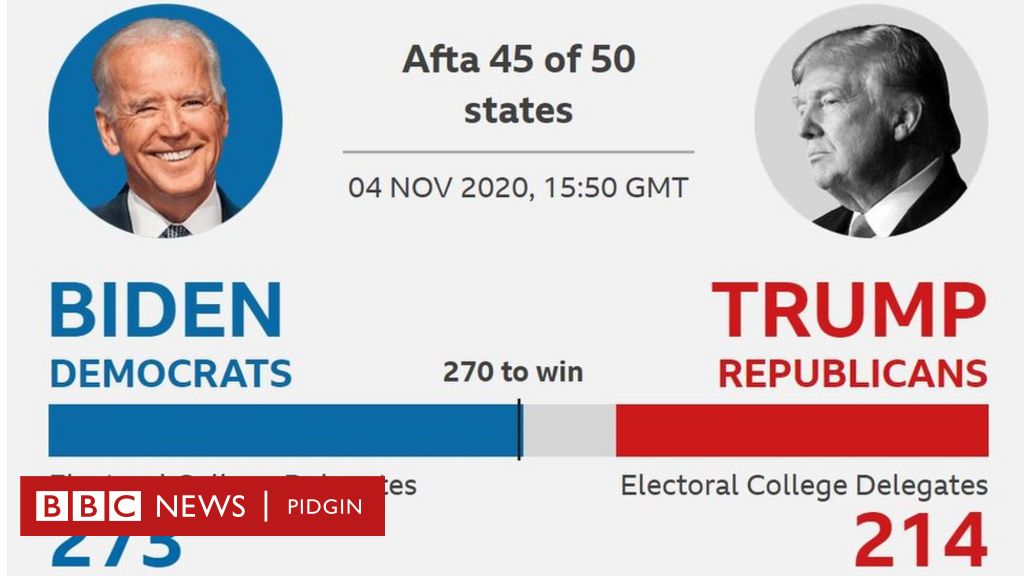

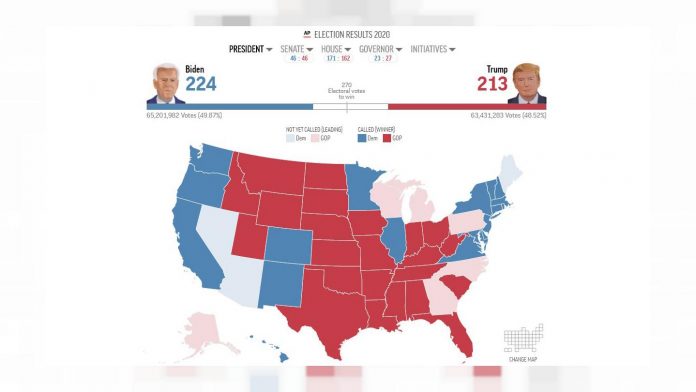

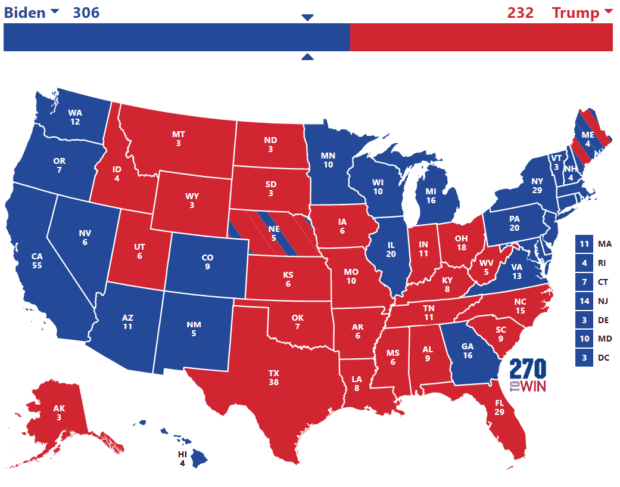

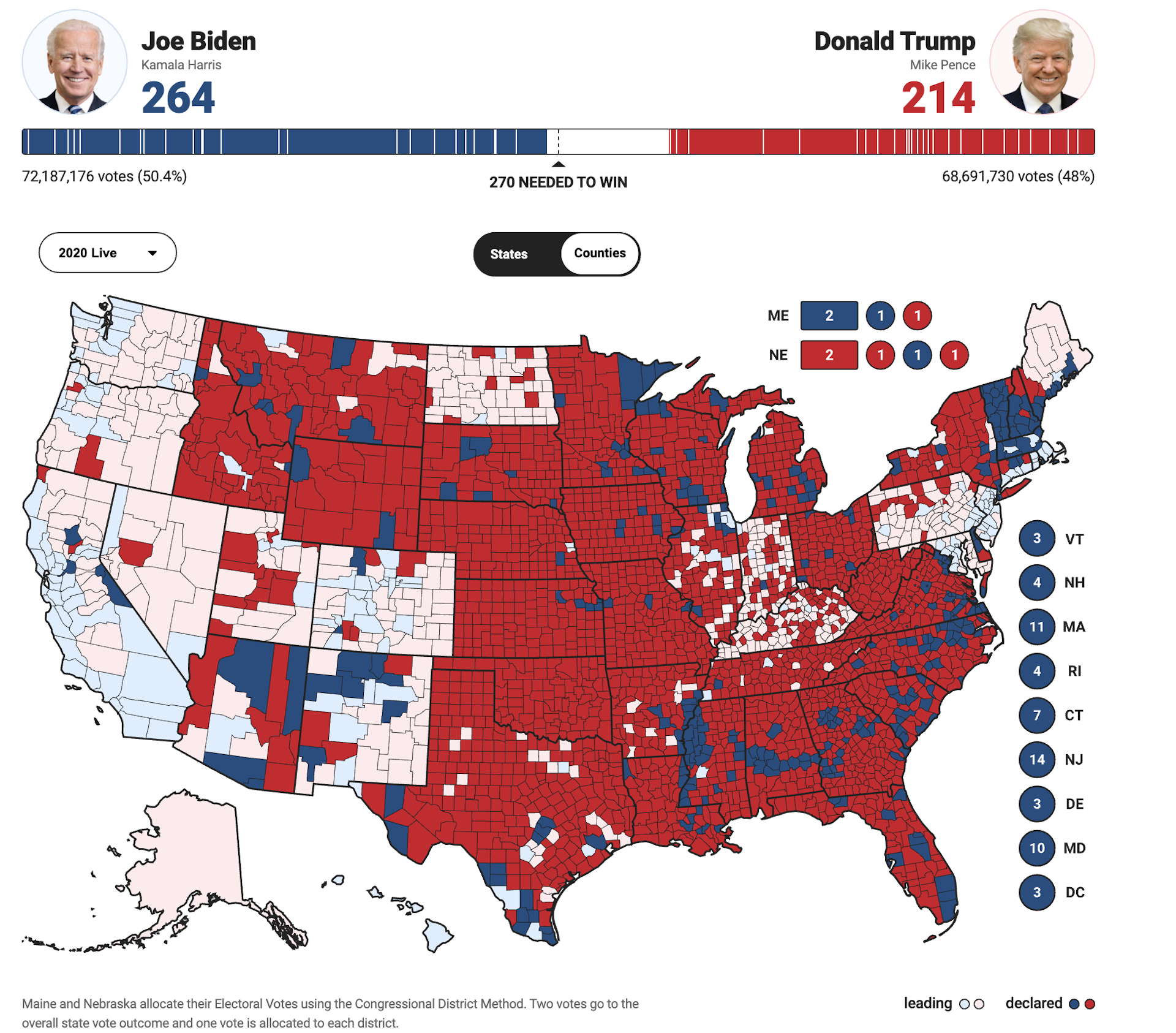

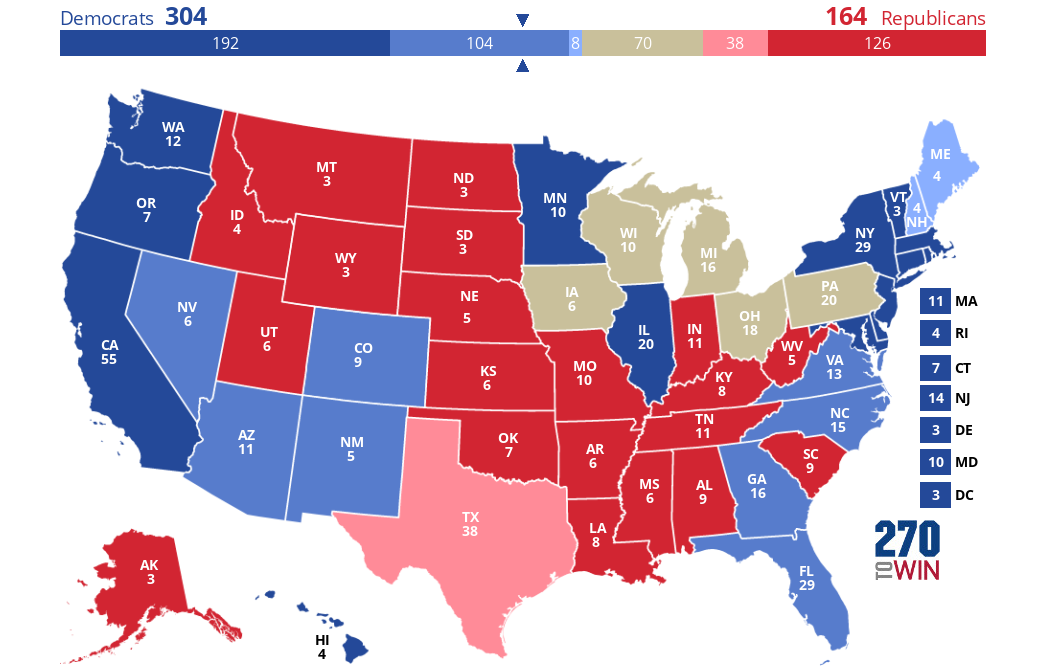

Biden won five swing states by 2 percent or less, but also won the US popular vote by more than 7 million, taking 51.3 percent of the popular vote to Trump's 46.8 percent. Biden won 306 electoral college votes, surpassing the 270 votes needed to become president and Trump's 232 votes. These lawsuits were an effort to block the secretaries of state from certifying results and deny Biden the electoral votes needed to win the presidency. Despite the Trump campaign's claims of widespread irregularities, the campaign failed to produce sufficient evidence, and the dozens of lawsuits, including one to the Supreme Court, were dismissed. In addition, election officials and state governors in every state Trump contested, including Republicans, stated there had been no evidence of widespread election fraud.

Instances have occurred in which the assignment of electors has created challenges in contested elections. In 2000, for example, a dispute over the results of the popular vote in Florida continued for a month after the general election and ultimately reached the US Supreme Court. The court's ruling halted an ongoing recount in the state and allowed Florida's secretary of state to certify the existing election results, which awarded twenty-five electoral votes to Republican candidate George W. Bush. Florida's votes pushed Bush's total electoral votes to 271, enough to win the presidency. Democratic candidate Al Gore won the national popular vote by 543,895 but lost the electoral vote by just five electors because he lost the popular vote in Florida by an estimated 537 votes—less than 0.01 percent of total votes cast nationwide. The outcome of the 1800 presidential election was so ardently contested that it was decided by the U.S.

The Democratic-Republican Party ticket of Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr won the popular vote against incumbent Federalist President John Adams and his running mate Charles C. Pinckney. However, Jefferson and Burr each received the same number of electoral votes to become president. House of Representatives selected the president with the loser becoming vice president. After 35 tied House votes, a 36th vote finally elected Jefferson as president and Burr as vice president.

In the election's aftermath, Congress passed and the states ratified the 12th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution requiring the electoral college to cast separate votes for president and vice president, thus ending the practice of awarding the presidency to the candidate with the most votes and vice-presidential title to the runner up. Every four years in the United States, the electoral college system is used to determine the winner of the presidential election.

In this system, each state has a fixed number of electors based on their population size, and these electors then vote for their candidate with the most popular votes within their state or district. Since 1964, there have been 538 electoral votes available for presidential candidates, who need a minimum of 270 votes to win the election. Because of this system, candidates do not have to win over fifty percent of the popular votes across the country, but just win in enough states to receive a total of 270 electoral college votes. However, critics argue that this system does not represent the will of the majority of American voters, and that it encourages candidates to disproportionally focus on winning in swing states, where the outcome is more difficult to predict.

The winner of some presidential elections have been decided by a very small number of popular and/or electoral votes and the candidate winning the most popular vote does not always become president. In the 1960 presidential election between John F. Kennedy and Richard M. Nixon , Kennedy won the popular vote by just .17 percent. Nixon won 26 states compared to Kennedy's 22 state win, but Kennedy prevailed with 303 electoral votes.

The 1876 presidential election was even closer with Republican Rutherford B. Hayes losing the popular vote to Democrat Samuel J. Tilden by 3 percent; however Hayes defeated Tilden by a single electoral vote to become president. More recently, Democratic candidate Al Gore lost the 2000 presidential election to Republican George W. Bush despite winning the popular vote by approximately 530,000 votes. In 2016, Republican Donald Trump won the electoral vote and presidency, but Democrat Hillary Clinton won the popular vote by approximately 2.8 million. The Constitution gives states full control over how they allocate their electoral votes. The current winner-take-all method, in which the winner of the statewide popular vote wins all of that state's electoral votes, is a choice—and states can choose differently.

Under the National Popular Vote interstate compact, states choose to allocate their electoral votes to the candidate who wins the most popular votes in all 50 states and DC. This compact takes effect only when enough states sign on to guarantee that the national popular vote winner wins the presidency. That means states with a combined total of 270 electoral votes—a majority of the Electoral College—must join the compact for it to take effect. While many U.S. voters may not realize it, when they go to the polls, it's to elect their president and vice president indirectly.

Every four years, political parties select electors who will vote for the party's candidate in the Electoral College. A vote for a candidate is actually a vote for their party's slate of electors, who cast their official votes in the days and weeks after Election Day. Since 1964, there have been 538 electoral votes in all, and a candidate must win more than half—at least 270—to win the presidency. The National Popular Vote plan guarantees election of the presidential candidate who receives the most popular votes in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

It creates an agreement among states to award all of their electoral votes collectively to the presidential candidate who wins the national popular vote. This agreement takes effect only once the participating states together hold a majority of electoral votes --guaranteeing that the winner of the national popular vote will win an Electoral College majority. Some of the United States' greatest statesmen, dominating personalities, and eloquent orators lost heartbreaking elections that took days or weeks to finally decide. For example, Declaration of Independence author Thomas Jefferson lost the 1796 election to John Adams before he was elected president in 1800 and reelected in 1804.

In 1824, Andrew Jackson won more of the popular and electoral college votes than other candidates, but lacked a majority. Jackson returned 4 years later to defeat Adams in 1828, and won a landslide victory against Henry Clay in 1832. William Jennings Bryant lost the 1896 and 1900 presidential elections to William McKinley and the 1908 contest to William H. Taft despite being one of the most skilled debaters and passionate orators in American history. Four decades later, Harry S. Truman surprised many Americans—including Republic challenger Thomas E. Dewey and analysts at the Chicago Tribune —to win the 1948 presidential election. More recently, incumbent President George H.W. Bush lost the 1992 presidential election despite a 91 percent approval rating 1 year earlier following the United States' Operation Desert Storm victory. NPV would ensure that the presidential candidate receiving the most votes throughout the country would be elected president.

The votes in every state and jurisdiction allocating electoral votes would be counted to determine the winner. Whether or not a state enters the NPV agreement, its voters would have a vote equal to everyone else's in selecting the president. For example, if Ohio does not approve the compact, the votes cast in Ohio would still be part of the national popular vote totals that would determine the winner of the presidency.

Those who oppose the Electoral College system disagree with Madison's reasoning and argue that a system of direct voting reflecting the will of the majority of voters is a better system for electing a president. Such critics question whether the Electoral College results are truly representative of the people. In five elections in US history—1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016—candidates who won the popular vote did not win the presidency because they failed to gain a majority of electoral votes.

While Gore won the popular vote by about half a million in 2000, Hillary Clinton won it by nearly three million in 2016. That year, Trump lost the popular vote by the biggest margin of any other US president who in turn won the Electoral College and the presidency. The disparity led to calls to abolish or reform the Electoral College.

Most states require that all electoral votes go to the candidate who receives the most votes in that state. After state election officials certify the popular vote of each state, the winning slate of electors meet in the state capital and cast two ballots—one for Vice President and one for President. Electors cannot vote for a Presidential and Vice Presidential candidate who both hail from an elector's home state. For instance, if both candidates come from New York, New York's electors may vote for one of the candidates, but not both.

In this hypothetical scenario, however, Delaware's electors may vote for both New York candidates. This requirement is a holdover from early American history when one of the country's major political fault lines divided big states from small states. The founders hoped this rule would prevent the largest states from dominating presidential elections. Under NPV, the Electoral College would remain the actual institution that elects the president, but would play a secondary role to the all-important national popular vote. Currently, the Electoral College serves to ratify the separate popular votes of the 50 states and the District of Columbia, with 48 states awarding electoral votes to the electors associated with the winner of the popular vote in that state.

Under NPV, the Electoral College would instead ratify the national popular vote by having participating states award votes to the electors associated with the slate of the national popular vote winner. This article offers a history of the Electoral College, including a serious effort in 1969 to eliminate it from the electoral process. The author argues that the College has never functioned as the framers of the Constitution intended and in practice favors some states over others in determining the winner of presidential elections. In his characteristically optimistic concession, Taft stated that, "No one candidate was ever elected ex-President by such a large majority."

In 48 states and the District of Columbia, when a candidate for president wins a state's popular vote, that party's slate of electors will be the ones to cast the vote for president of the United States in December. If President Donald Trump wins the state's popular vote on Nov. 3, the 29 electors nominated by the Republican Party in Florida will be selected. These 29 people will gather on Dec. 14 to cast their votes for president of the United States. An extremely close state election can be hard to finalize in time for the December meeting of the Electoral College, yet such a close election in a state is far more likely than a razor-thin vote in the national popular vote. "Third-party" candidates can disrupt elections and draw votes away from more popular candidates, but they have never won a presidential election in the United States.

H. Ross Perot won 18.9 percent of the popular vote—a record for an Independent Party candidate—in the 1992 presidential election that saw Democrat William J. Clinton defeat incumbent Republican President George H.W. Bush. Despite the strong showing at the polls, Perot did not receive any electoral college votes. Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt won the 1936 presidential election with the greatest landslide victory in American history.

Winning 60.8 percent of the popular vote and 523 (98.5 percent) of the electoral vote to defeat Republican challenger Alfred M. Landon. Forty-eight years later, President Ronald Reagan defeated Democratic candidate Walter Mondale with 58.8 percent of the popular vote and a record 525 (97.6 percent) of the electoral college votes. In the current Electoral College system, the presidency is awarded to the candidate who wins at least 270 of the 538 available electoral votes. The Constitution gives state legislatures the right to choose how presidential electors are chosen.

Since the 19thcentury, each state has awarded its electoral votes to the winner of the popular vote in that state. But under the NPV system, states would commit to award their electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote instead. Since the 1860 election, U.S. presidential elections have been dominated by candidates affiliated with the Democratic and Republican parties.

While the electoral votes decide the winner of the election, these are generally decided by the winner of the popular vote in each state , and the winner of the nationwide popular vote does not always go on to win the electoral vote. Interestingly, there have been a number of occasions where the winner of the popular vote did not go on to win the electoral vote, for example in the 2016 election, or, most famously, in 2000. In upcoming elections, one could just as well flip a coin as use the Electoral College to decide the winner if the popular vote margin is inside a still-comfortable 500,000 votes. The winner-takes-all approach of most states has led to the phenomenon of swing states.

Swing states are states in which the popular vote is determined by a very narrow margin. In 2016 swing states were key to Donald Trump's unexpected victory against Hillary Clinton. Though he lost the national popular vote by 2.9 million, and Clinton won 48 percent of the overall US popular vote while Trump won 45.9 percent, Trump gained 304 Electoral College votes by capitalizing on narrow wins in swing states. Trump won Michigan by less than 1 percent to gain sixteen electoral votes, Wisconsin by 1 percent to gain ten electoral votes, and Pennsylvania by 1.2 percent to gain twenty electoral votes.

News & World Report, Trump's success depended largely on his ability to win in a number of previously Democratic states by very small margins. While former US president Barack Obama won two states by 2 percent or less in 2012, Trump won six states by 2 percent or less in 2016. The president and vice president of the United States are formally elected through an electoral college. Members ("electors") of this electoral college are chosen through the popular vote in each state, and to be elected president a candidate must receive a majority of the electoral votes. If no candidate receives a majority, the president is elected by the House of Representatives, which may choose among the three candidates with the most electoral votes. On Election Day, people vote for their preferred candidate's electors, who are chosen by political parties or independent candidates before the election.

Those individuals, collectively the Electoral College, then cast votes for president and vice president, usually representing the choice their state's voters made. National Popular Vote is an interstate compact leveraging the state power to award electors under Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution. The compacting states agree that, once states with 270 electoral votes have passed the bill, they will all award their electors en bloc to the candidate who wins the most popular votes across all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

Leading thinkers at the Constitutional Convention like James Madison preferred a national popular vote for president, but accepted the Electoral College for political and administrative reasons that no longer exist today. For example, southern states with large numbers of slaves knew they would be big winners with the Electoral College system. Slaves were denied voting rights, as were nearly all women, racial minorities, and citizens not owning property, but were still counted for the purposes of determining a state's number of congressional seats and electoral votes. In 1800, Virginia had fewer free citizens than Pennsylvania and New York, but had more electoral votes due to slaves representing 39% of its population. It is no coincidence that four of our first five presidents were from Virginia. Evidence of their willingness to reform the Electoral College comes from the 12th amendment to the Constitution, adopted in 1804.

In the first four presidential elections, presidential candidates ran without official running mates for vice-president. If gaining support from a majority of electors, the candidate earning the most votes became president, while the candidate with the second-most votes became vice-president. In 1796, John Adams won the presidency, but his electors withheld just enough of their second votes for his running mate Thomas Pinckney to allow Adams' opponent Thomas Jefferson to finish second and become vice-president.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.